Ageing in displacement:

The East Timorese diaspora in indonesia

Victoria Kumala Sakti

As the world’s population ages, humanitarian crises increasingly impact the lives of older people. Yet, research focusing on older refugees is a field that is still emerging. There is a critical need to examine the ageing dimensions of forced migration, particularly from older persons’ perspectives and subjectivities. While most research on this phenomenon has focused on the experiences of those living in the global North, much less has been written about the predicaments of older people living in refugee camps, through displacement, and exile in developing countries located in the global South.

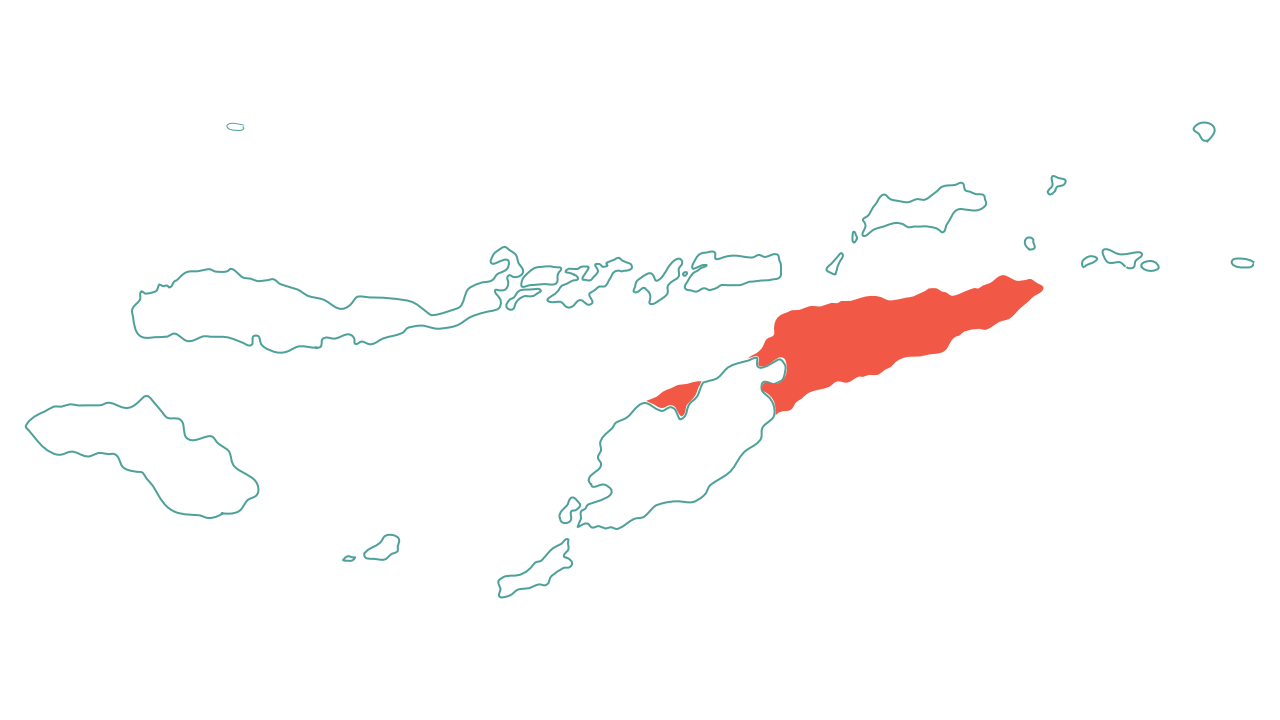

Around 90 per cent of displaced populations worldwide live in increasingly protracted situations in countries located in developing regions of the world (Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, 2016). In Indonesia, for instance, East Timorese diasporas have lived for over twenty years in former refugee camps and new settlements. While they have received Indonesian citizenship, East Timorese groups face discrimination, social exclusion, poverty, and live amid ongoing displacement conditions.

As the world’s population ages, humanitarian crises increasingly impact the lives of older people. Yet, research focusing on older refugees is a field that is still emerging. There is a critical need to examine the ageing dimensions of forced migration, particularly from older persons’ perspectives and subjectivities. While most research on this phenomenon has focused on the experiences of those living in the global North, much less has been written about the predicaments of older people living in refugee camps, through displacement, and exile in developing countries located in the global South.

Around 90 per cent of displaced populations worldwide live in increasingly protracted situations in countries located in developing regions of the world. In Indonesia, for instance, East Timorese diasporas have lived for over twenty years in former refugee camps and new settlements. While they have received Indonesian citizenship, East Timorese groups face discrimination, social exclusion, poverty, and live amid ongoing displacement conditions.

Timor-Leste was a Portuguese colony for over four centuries before Indonesia illegally annexed the territory in the mid-1970s. Throughout the Indonesian occupation, many East Timorese families became divided politically, often out of the necessity to survive. Older adults, more than their younger family members, have lived through multiple periods of displacement. Kinship ties, ancestral beliefs and significant places, such as the lineage house and grave sites, structure East Timorese societies and continuously draw East Timorese diasporas in West Timor to return or visit.

West Timor is part of Indonesia’s East Nusa Tenggara (NTT) province. In 1999, it received around 250,000 East Timorese refugees. UNHCR ended their refugee status following the gradual repatriation of nearly 90 per cent of the refugees back to Timor-Leste in 2002. A few years later, the Indonesian government ended the refugee status of those who chose to remain and granted them citizenship. Multigenerational East Timorese families live in former refugee camps, resettlement sites and within local dwellings across West Timor. Many families strive to maintain kinship and cultural ties to extended family and ancestral landscapes in Timor-Leste.

Please click on one of the hotspots

Displacement context

In 1999, widespread violence broke out in Timor-Leste when they voted for independence from Indonesia, which occupied the country for twenty-four years. During the chaotic withdrawal, the Indonesian military and their East Timorese militias displaced 250,000 people to West Timor. While most refugees have now returned to Timor-Leste, many families stayed behind. Some worked for the military and their family feared revenge should they return to the homeland. Today, more than 88,000 East Timorese currently live across West Timor. These include those who worked for the Indonesian government, military and police force who have reached or are now approaching retirement age (58 years old). Apart from this formal sector, many East Timorese are subsistence farmers and work as sharecroppers on land owned by local West Timorese.

Research aims and questions

Narratives and memories

At the heart of this study are older people’s narratives and memories of conflict and displacement. It explores the ways that they reconstruct life away from, and in conjunction with, their ancestral lands and people back home, as well as with family members of different ages.

Time, ageing bodies, and borders

It asks what it means to grow older in this context, i.e., out of the preferred place and across transnational space. It also looks at the effect of time, and the gradual social and cultural changes that the elderly encounter in their new settings in the ways that they navigate later life decisions, including on matters of death and burial.

Intersections of ageing and mobilities

The study examines the intersections of ageing and mobility in people’s movements across re-established national borders and the question of return. It traces the ways in which colonial legacies, political transformations and ongoing economic inequalities shape people’s experiences of ageing and mobilities across a South-South migration trajectory.

Research aims and questions

Narratives and memories

At the heart of this study are older people’s narratives and memories of conflict and displacement. It explores the ways that they reconstruct life away from, and in conjunction with, their ancestral lands and people back home, as well as with family members of different ages.

Time, ageing bodies, and borders

It asks what it means to grow older in this context, i.e., out of the preferred place and across transnational space. It also looks at the effect of time, and the gradual social and cultural changes that the elderly encounter in their new settings in the ways that they navigate later life decisions, including on matters of death and burial.

Intersections of ageing and (im)mobilities

The study examines the intersections of ageing and mobility in people’s movements across re-established national borders and the question of return. It traces the ways in which colonial legacies, political transformations and ongoing economic inequalities shape people’s experiences of ageing and mobilities across a South-South migration trajectory.

More than 88,000 East Timorese currently live across West Timor. These include those who worked for the Indonesian government, military and police force who have reached or are now approaching retirement age (58 years old). Apart from this formal sector, many East Timorese are subsistence farmers and work as sharecroppers on land owned by local West Timorese.

East Timorese diasporas have lived for over twenty years in former refugee camps and new settlements. While they have received Indonesian citizenship, East Timorese groups face discrimination, social exclusion, poverty, and live amid ongoing displacement conditions.

East Timorese older adults develop strategies in dealing with family separation and exile from the ancestral land. They engage in translocal practices across state borders through return visits, ancestral rituals, and memories of place. They also carry out place-making activities in the new settlement, such as nurturing diasporic and support networks, gardening and choosing the new place as the future place of burial.